Countless species of flora and fauna have been lost in what is now being labeled as the Anthropocene extinction event. Fortunately, two local species have not only escaped from the brink of extinction but have rebounded as humans have improved our behavior. This success story holds valuable lessons in how we can save other imperiled species through our cultural practices. The story of the Coontie plant (Zamia integrifolia) and Atala butterfly (Eumaeus atala) is one that I hope inspires you to implement Florida-Friendly Landscaping practices. Together we can transform our landscapes from biological deserts to biodiverse oases for our native flora & fauna.

A Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Tale of Survival and Resurgence Part I: Coontie Cycads

Native to the southeastern United States, the Coontie (Zamia integrifolia) plant has a fascinating history deeply intertwined with the land and its inhabitants. For thousands of years the plant was used by Native American cultures, but it was later driven to near extinction due to commercial exploitation by European settlers. Today, it is having a resurgence as a Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ staple. One thing has been constant, the Coontie has been an important plant to humans in Florida.

Ancient History

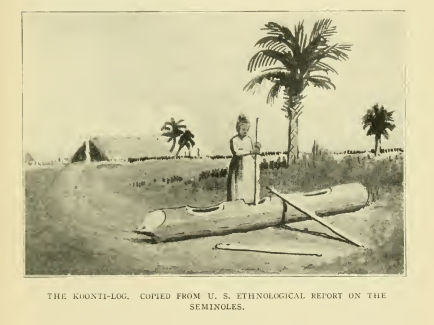

Native American tribes, including the Calusa and later Seminoles, recognized the ethnobotanical value of Coonties. They initially utilized various parts of the Coontie for different purposes. The plant’s starchy underground stems, known as rhizomes, were ground into a staple flour used for making bread, porridge, and cakes. This is how the plant received its common name, Coontie, which roughly means ‘white bread’ in the Seminole language. Additionally, the rhizomes were dried and used for medicinal purposes, treating ailments such as stomachaches and skin irritations.

When Europeans arrived in Florida, they found Coonties to be extremely prevalent along rivers and along the coast, which suggests that the Coontie might have been widely planted by the Native American communities who were also found in these areas.

One such area was Coontie hatchee in what is modern Broward County, which translates to ‘River of Coontie’, named for its extreme abundance of the plant. This valuable plant being found in such abundance captured the attention of William Cooley, who founded the New River Settlement and brought in African slaves to harvest the plant. This incursion did not sit well with the indigenous tribes who relied on Coontie as their staple food source. In 1835 this issue and other disputes led to the massacre of Cooley’s settlement, which was abandoned until a fort was created in the area. A little old fort named after Major Lauderdale, the leader of the army that was sent down to hunt down the local Seminoles in the Second Seminole War.

Exploitation to the Brink

After the Seminole tribe was driven into the Everglades with less than 200 surviving members, commercial interests once again became interested in the Coontie plant. Factories sprung up throughout Florida to process it. Up until the 1930s several factories were processing 10-20 tons of the plant every day! Myriad different uses were found for the starch rich flour produced from the plant, including the flour being utilized as a core component of WWI ration packs and animal crackers.

Coontie plants take close to a decade to reach a harvestable size, so it was never farmed, rather Coonties were collected from natural areas. This unsustainable commercial exploitation led to the near extinction of the plant. As settlers expanded their territories, the Coontie’s habitat was fragmented, further reducing it’s population. These combined factors pushed the Coontie plant to the brink of extinction, with significant populations lost throughout its native range.

Conservation Efforts

In the 20th century, as awareness grew about the importance of preserving native species, efforts were made to save the Coontie plant from disappearing altogether. Botanists, conservation organizations, and passionate plant enthusiasts recognized the ecological and historical value of the Coontie, leading to dedicated conservation initiatives. Research was conducted to better understand the plant’s biology, reproduction, and ecological role, which further aided in its protection.

During this time frame the Coontie was labeled by the state of Florida as a Commercially Exploited Plant and gained the protected status it holds to this day. This imperiled status prevents people from harvesting it from the wild, but does not protect it as a landscape plant. As modern landscapers shifted towards plants that utilize less fertilizer and less water, Coontie was finally recognized for this crucial use. Adaptable, low-maintenance, drought-tolerant, with evergreen tropical fronds; this plant has surged in popularity. You commonly see the plant serving as an excellent foundation or accent plant in various landscape designs.

The Coontie’s status as a rare native plant also adds an ecological dimension to any landscape. Encouraging local biodiversity and supporting the caterpillars of the rare Atala butterfly. You are not only beautifying your surroundings but also contributing to the conservation efforts of these imperiled species.

Conclusion

The history of the Coontie plant is a testament to the interconnectedness of the natural world and human behavior. Human activities, such as our consumption of natural resources and our landscaping practices, can greatly impact local ecosystems. While nothing compares to protected public lands, we can help our imperiled species if we make educated landscaping decisions to combat habitat fragmentation and preserve biodiversity.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT in order to help build out the blogpost. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication. Historical information was added by author and can be found in the sources listed below.

Sources used:

• https://www.fortlauderdale.gov/Home/ShowDocument?id=2740&lang=en

• https://www.loc.gov/item/12024179/

• https://mail.fnps.org/assets/pdf/palmetto/hammer_roger_l_the_coontie_and_the_atala_hairstreak_vol_15_no_4_winter_1995.pdf

• https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/trees-and-shrubs/palms-and-cycads/coontie.html

• https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/hort/2021/03/11/the-coontie/

• https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FP617

Source: UF/IFAS Pest Alert

Note: All images and contents are the property of UF/IFAS.