In terms of diversity and abundance, the Phylum Arthropoda is the most successful in the Animal Kingdom. Between them all, there are over one million species. They can be found in all habitats, from the deepest part of the ocean to the highest places in the mountains, from the polar region to the most extreme deserts. Most are insects, but there are also arachnids, centipedes, millipedes, and the ones most common to the marine environment – the crustaceans. With the numerous species within this group, and new ones being discovered all the time, the classification of arthropods is constantly changing. Currently Crustacea is considered a subphylum and there are about 30,000 species within.

Photo: UF IFAS

There are several keys to the success of arthropods. Number one, their shell. It was seen with the mollusk that having a hardshell to protect your soft body was a winner. However, mollusk make their shells from heavy calcium carbonate. Though this provides excellent protection against most predators, it did slow them down considerably making it much easier for predators to catch them. It is understood that in the world of defense, speed is important. The arthropods make their shells from a strong, but much lighter material called chitin. This material is strong but serves as the creatures’ exoskeleton and must be shed periodically as the animal grows.

Number two, their legs. The name “arthropod” means jointed foot and one glance at the legs of any of these, you will see why scientists call them this. To increase speed animals, need to break contact with the surface of the ground. Birds are the best, lifting off and flying – the fastest form of location there is. The slug-like mollusks have their entire bodies in contact with the sediment, as the “slug” along the bottom of the sea. Many creatures have developed legs and walk, this is the case of the arthropods. Some hop great distances, like the flea. Others can actually swim, like blue crabs. And many of the insects have wings and can fly. But these jointed legs, along with a lighter shell, have been very effective defense for these creatures.

Number three, their sense organs and brain. Though not as intelligent as octopus and squid, arthropods are very aware of their environment and very quick to respond to trouble or a food source. Drop a piece of cheese during a picnic and see just how fast the ants find it. Heck don’t drop the piece of cheese and see how quickly they find it! These animals have a series of hairs, bristles, and setae connected to their shell that can detect movement and pressure changes in the environment. There are canals, slits, pits, or other openings in the shell that can detect odors. And then they have their compound eyes. Compound in the sense there are more than one lens. Each lens does provide an image of the target (in other words, they do not see 100 images of you) but rather each provides a level of light intensity sort of like individual pixels in a computer image, or the image we see when the camera displays “squares” of light so that you cannot read someone’s license plate, or the logo on their t-shirt – we see this on TV news and shows often. Compound eyes do not produce as clear an image as our eyes, but they are MUCH better at detecting motion, and there is an advantage to this. Try stomping on a cockroach, or swatting a fly, and you will see what I mean.

And number four, a high reproductive rate. You see this in many of the “prey” type species. Most arthropods are dioecious (males and females) and can produce millions of offspring at rates that you could never consume them all. So, they survive and can quickly support gene flow and adaptation. These are well designed animals.

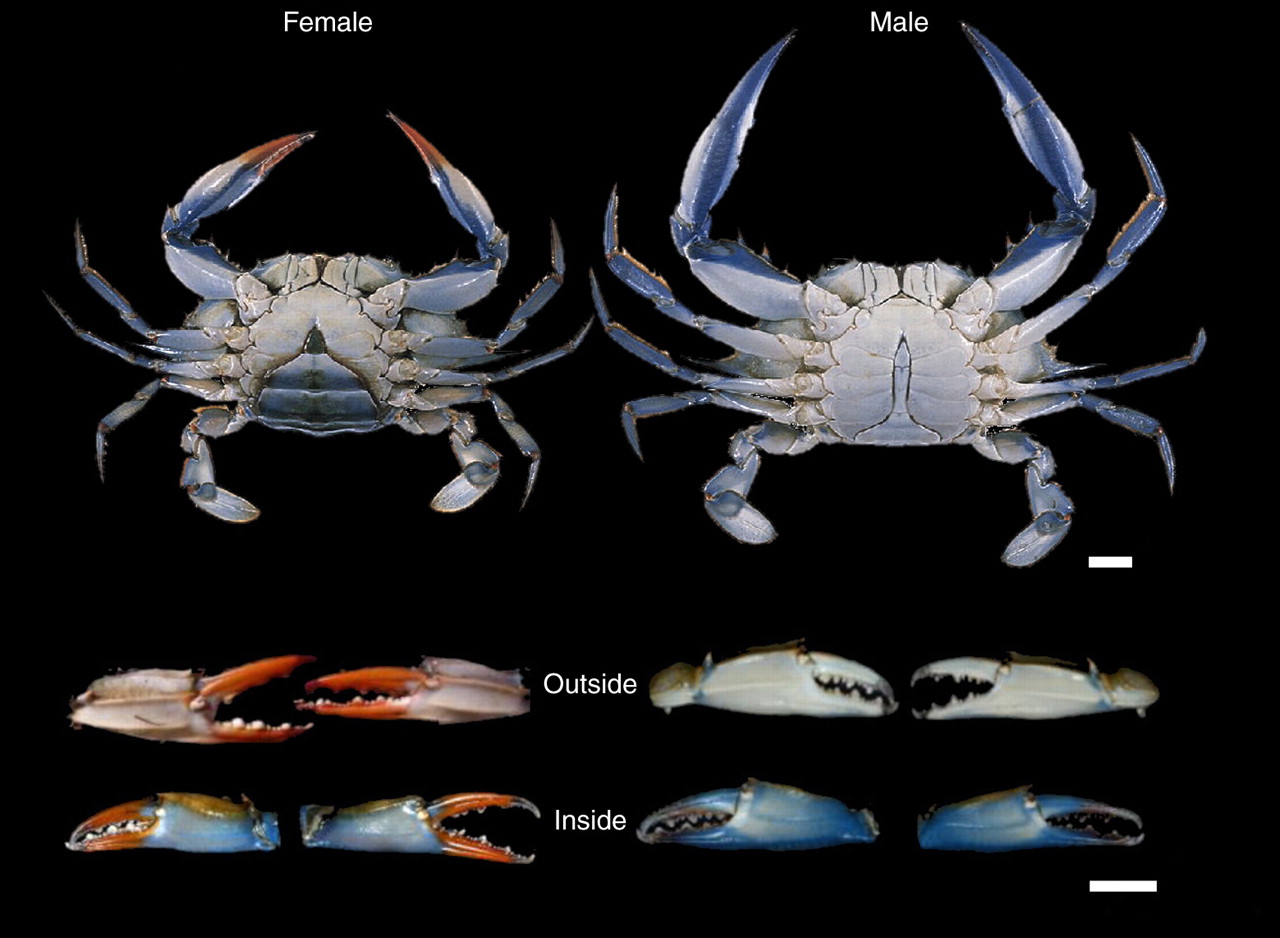

Photo: Molly O’Connor

In the crustacean world we find several groups. They differ from their arthropod cousins in that they have 10 jointed legs, and two sets of antenna (one set long, the other short). They include at least 30,000 species including the shrimplike cephalocarids, the shrimplike branchipods, the shrimplike ostracods (common in the deep sea), the roachlike copepod (part of the plankton we spoke about in another article in this series), the mystacocards, branchiurans, the familiar barnacles, krill, the roachlike isopods, flea like amphipods, and the most familiar of the group – the decapods – which includes the crabs, shrimps, and lobsters. It is this last group we will focus on.

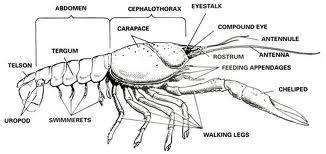

There are three basic body parts to an arthropod. The head, thorax, and abdomen. In crustaceans the head and thorax are fused into one segment called the cephalothorax (the head of a shrimp or crawfish). The abdomen is what most call the shrimp and crawfish tail (the part we usually eat).

Image: Study Blue

Crabs are the ones we most often encounter when exploring the seagrass beds. Not that the others are not abundant, they are, they are just not seen. They differ in that their abdomen is curled beneath their cephalothorax. The most commonly encountered is the famous blue crab (Callinectes sapidus). Most crabs have modified two of their 10 legs into chelipeds (claws) and most folks seeking crabs for dinner are aware of these claws. The blue crab belongs to a group called the protunid crabs which have modified two additional legs into swimming paddles – they can swim. They are often found crawling around the edges, and within, the seagrass searching for food. When detected over sand, they quickly bury themselves and sometimes people step on them not knowing they are there. When spooked they often will emerge with chelipeds extended and when the time is right, will scurry off running sideways with one cheliped pointed at you. They can get quite large and are a popular fishing target for both recreational and commercial fishermen. The males (the ones with the long then telson on their curled tailed) are more common in the upper estuaries. The females (the ones with the more round telson) frequent the lower bay. During breeding season, the males will move to the lower estuary to find a female. Once found he will crawl on her back and “ride” for a couple of days in what commercial fishermen call “doublers”. At some point the male will provide a tube filled with sperm called a spermatophore to the female. He then moves on. The female will store the spermatophore until she feels it is time to fertilize the eggs, then does so. The eggs begin to develop beneath her abdomen in a spongy looking mass. Early in development the mass is an orange color. Closure to hatching it is brown. Females carrying this spongy mass are called gravid and are illegal to harvest in Florida. The larva will be released in the millions as tiny plankton and go through several life stages before becoming young crabs and starting the whole story again. These popular crabs live for about five years.

Another crab found in the grassbeds is the spider crab (Libinia dubia). This crab does resemble a spider, is slow moving, and very hard to see. It has small chelipeds and feeds on debris and organic material collected by the grasses. They too can get quite large and resemble the king crabs harvested in Alaska.

Stone crabs (Menippe mercenaria) are more often associated with rocky bottoms, or artificial reefs, but they have been found in burrows and crevices within grassbeds. The have wide-stocky chelipeds, which is a favorite with some seafood lovers. Those in the grassbeds do not get as large as those found around the reefs of south Florida, where they support a large commercial and recreational fishery.

The hermit crab is a common resident of grassbeds. The most frequently encountered is the striped hermit (Clibanarius vittatus). Like all hermit crabs, they lack an external shell covering their abdomen and must cover their tail with an empty mollusk shell. Their curled abdomen can grab and wrap around the columella within the mollusk shell and carry around their new home. These hermits have been found in a variety of mollusk shells and are found roaming the beaches at low tide feeding on organic debris and cleaning the grassbeds.

One crab that is often associated with seagrasses is not actually a crab at all. The horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) lacks antenna and is more closely related to the arachnids. This ancient mariner has been plowing the bottoms of estuaries for over 400 million years. They resemble stingrays with their elongated telson and feed on a variety of small invertebrates both in the grassbeds, and in other estuarine habitats. They are quite common in the eastern panhandle and seem to be making a recovery in the western end.

Photo: Amanda Mattair

Though rarely seen, shrimp are very prolific in our seagrass beds. Pulling a seine or dip net through the grass will expose their presence, usually in high numbers. The most commonly collected species are those known as grass shrimp (Palaemonetes sp.). There are a few species, and all are small and mostly translucent, though one is a brilliant green. Feeding on organic debris within the grassbed these little guys are an important food source for the larger members of the community.

The more famous of the shrimp group are the brown and white shrimp. These are the species we find on our dinner plates and are one of the most popular commercial species in the country. Brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus aztectus) are also known as bay shrimp and “brownie”. They are a darker brown than the white shrimp and their uropod (the fan on the tail of the shrimp) is lined in a red color. They do not get as large as the whites and are very popular for fried and steamed dishes. The white shrimp (Litopenaeus setiferus) is a larger shrimp, is lighter in color (“white”), and their uropod is lined with a neon green color. Both of these commercially important species spend their juvenile and young adult days in the grassbeds of our estuaries. Later in the fall the adults move into the nearshore waters of the Gulf where they spawn and die. The planktonic larva drift back into the estuary with the incoming tide, finding the grassbeds and the cycle begins again.

Photo: FishWatch

The large diversity of crustaceans within the grassbeds speaks to the importance of this habitat to all marine life. Many are commercially important to the local economy and depend on a healthy ecosystem to survive. All the more reason to protect our grassbeds.

Source: UF/IFAS Pest Alert

Note: All images and contents are the property of UF/IFAS.