For centuries humans have been interested in what is on the bottom of the sea. Stories and legends arose of mermaids and magical cities like Atlantis. From the science side of things, the interest was there as well. In the mid-nineteenth century geology students were told the ocean floor was a featureless landscape made of sand, mud, and rock. It made since at the time. But one group of natural historians thought that the statements had no support and that a proper study of the ocean floor was needed. One of the leaders of this group was Charles Wyville Thomson.

Image” London Museum

You have to understand that Thomson, and others, were not the first to have thought this idea. The problem was HOW… how do you measure the depth of the oceans? What was missing was the technology to do the job. In 1872 Thomson became the chief scientist of what would become the first oceanographic expedition – the voyage of the HMS Challenger.

The voyage of the Challenger would cover the globe and take over five years to complete. At sea they developed methods for sampling water, measuring currents, sampling marine life, sampling the ocean floor, and measuring its depth. At that time, the only common method of measuring depth was to drop a large weight on a line and measure the line when it hit bottom. This is what the Challenger did and, surprisingly, when the German research vessel Meteor retraced Challenger’s trip using a new technology in the 1920s called SONAR, the Challenger depths were pretty close!

The Challenger found the ocean floor was anything but featureless. It was covered by some of the tallest mountains, and longest mountain ranges found on the planet. There were vast open plains, as once thought, but there were also deep tectonic trenches and canyons.

As you leaned over the bow of the “O 2” and looked into the Deep Blue, below you were large mountains and canyons, and it is hard to picture this looking into the clear cobalt blue water.

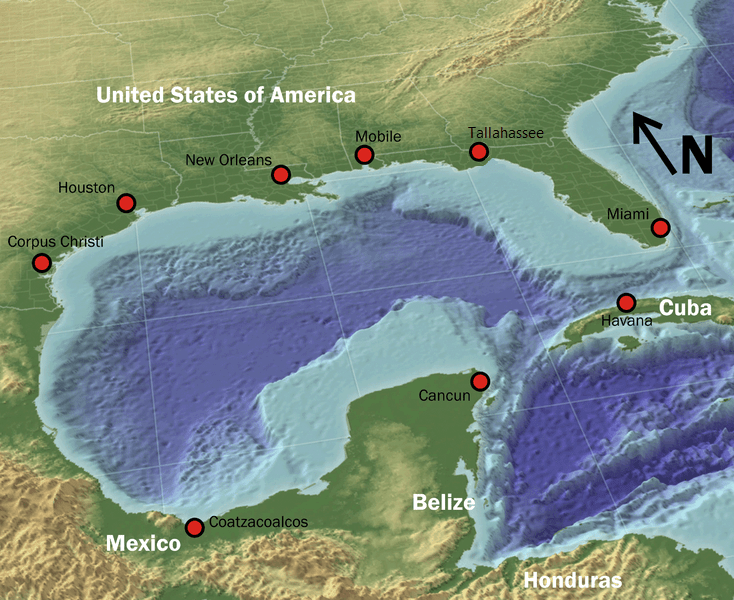

The Gulf of Mexico is similar to the great oceans in design. As you leave Pensacola and head due south you first cross over a large expanse of shallow area (appearing light blue on the map of the Gulf attached). Though the depth of this light blue area is hundreds of feet deep, relative to the deep ocean, it is shallow and is known as the continental shelf. The distance of the shelf offshore varies from one location to another. You will notice that near Pensacola is comes closer to shore than most other locations along the Gulf. This indention of dark blue color into the shelf near Pensacola is actually a submarine canyon known as the DeSoto Canyon. Most likely formed at a time when sea level was much farther offshore than where it is now, the canyon is now completely submerged.

As you reach the edge of the shelf (the light blue) you notice a sharp “drop-off” to the ocean deep – the REAL Deep Blue. This drop-off is known as the continental slope. You can see that the slope is somewhat gradual along the Texas coast but is a steep drop off the coast of west Florida and the Yucatan. You will also notice that the shelf is several hundred miles offshore of the coast of west Florida.

The Challenger used sounding lines, the Meteor used SONAR, modern vessels – like the “O 2” use a technology similar to SONAR and modern day depth finders. They all seem to agree. Even though we cannot see the ocean floor and the seamounts that lie there, the returning data suggest they are. It is not a featureless landscape.

But is it rock? Sand? Or Mud? What material makes up the ocean floor? To gather that information the oceanographers developed a simple technology called a grab. The idea is pretty simple. A large metal “grab” is set to open when it hits the ocean floor where it will close and “grab” a sample of the bottom. The earliest grabs were set by a notch on the metal arm that would release when the instrument hit the ocean floor. Some modern-day grabs use an electric powered piston to snap shut when fired by an operator on board.

Photo: Coastal Science NOAA

To deploy the grab, you would use a steam powered winch to lift it out of its carriage and drop it on the stern deck – hard hats and life jackets are a MUST. Here the “trap” would be set, and how that would happen would depend on the type of grab you were using. Once the “trap” was set, you would lift the grab using the winch and swing it over the catwalk on the side of the ship. Here a couple of people would grab the line and assist this large instrument over the side and slowly to the surface of the ocean.

Remember… while all this is going on, the ship is slowly rocking and rolling. So, the large metal grab suspended on a cable above the deck is swinging with the rocking ship. The team would often secure additional lines to the grab to help hold it steady as it was moved over the side. You had to be VERY careful when all this was going on. Remember… No One – NO ONE was allowed beyond the yellow line when equipment was being deployed and retrieved. This was why.

Once the grab was on the surface of the water you could release the winch and let her drop to the bottom. When it hit, the self-tripping mechanism would release the trap and close in on a sample of the ocean floor. The grab was then lifted back to deck, a lined secured, and you would carefully move the swinging instrument onto the deck. Here you would release/open the grab and your sample would be there.

Since the time of the Challenger oceanographers have been doing this. They have found mud, sand, silt, clay, even volcanic rock, and… coral. These grabs often collected a variety of benthic creatures at depths of 1000s of feet. This was a surprise to the first oceanographers, and we will discuss that in another Part of this series.

But for Finding the Bottom, we found it. It must be an amazing world down there. If we could only visit it… and you guessed, it – we have. That is another story.

Sea Stories…

Another thing I noticed as I was boarding the “O 2” were white rubber boots – the same type you see shrimpers wear. I did not have any, and did not think I needed any, but most of others did have them. A later found out why.

The stern and wet bay were both… wet. Not only was there water sloshing around in places, but there was also “fish juice”. Remember, we were collecting fish. I was wearing a pair of canvas boat shoes. My shoes quickly became saturated with this fishy water and smelled to high heaven! When leaving wet bay, others would kick their rubber boots off and jump into dry canvas shoes in the dry bay before heading to their cabin or galley. I had to wear my wet smelly shoes everywhere every day for a week.

Bring rubber boots!

Source: UF/IFAS Pest Alert

Note: All images and contents are the property of UF/IFAS.